Profile: Les Stone

Source: Digital Photographer

October 1, 2004

Digital Photographer chronicles the award-winning career and experiences of ZUMA Press photojournalist Les Stone. Below is the text from the five page spread as published in the October 1, 2004 issue.

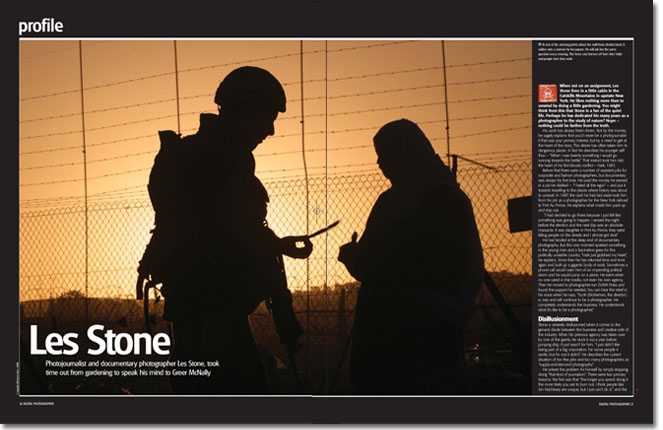

Cover Photograph: At one of the crossing points where the wall/fence divides Israel. A

soldier asks a woman for her papers. He will ask her the same

question every morning. The fence cuts farmers off from their fields

and people from their work.

Digital Les Stone

Photojournalist and documentary photographer

Les Stone, took time out from gardening to speak his mind to Greer

McNally

When not on an assignment, Les Stone lives

in a little cabin in the Catskills Mountains in upstate New York.

He likes nothing more than to unwind by doing a little gardening.

You might think from this that Stone is a fan of the quiet life.

Perhaps he has dedicated his many years as a photographer to the

study of nature? Nope nothing could be farther from the truth.

His work has always been driven. Not by

the money, he sagely explains that you'd never be a photojournalist

if that was your primary interest, but by a need to get at the heart

of the story. This desire has often taken him to dangerous places.

In fact he describes his younger self thus "When I was twenty

something I would go running towards the battle." That instinct

took him into the heart of his first bloody conflict Haiti, 1987.

Before that there were a number of assistant

jobs for corporate and fashion photographers, but documentary was

always his first love. He used the money he earned in a job he disliked

"I hated all the egos" and put it towards travelling to the

places where history was about to unravel. In 1987 the cash he had

laid aside took him from his job as a photographer for the New York

railroad to Port Au Prince. He explains what made him pack up and

ship out.

"I had decided to go there because I just

felt like something was going to happen. I arrived the night before

the election and the next day was an absolute massacre. It was slaughter

in Port Au Prince, they were killing people on the streets and I

almost got shot." He had landed at the deep end of documentary photography.

But this one moment sparked something in the young man and a fascination

grew for this politically unstable country. "Haiti just grabbed

my heart", he explains. Since then he has returned time and time

again and built up a gigantic body of work. Sometimes a phone call

would warn him of an impending political storm and he would jump

on a plane. He went when no one cared in the media, not even his

own agency. Then he moved to photographer-run ZUMA Press and found

the support he needed. You can hear the relief in his voice when

he says, "Scott (McKiernan, the director) is, was and will continue

to be a photographer. He completely understands the business. He

understands what it's like to be a photographer."

Disillusionment

Stone is severely disillusioned when it

comes to the general divide between the business and creative side

of the industry. When his previous agency was taken over by one

of the giants, he stuck it out a year before jumping ship. It just

wasn't for him. "I just didn't like being part of a big corporation.

For some people it works, but for me it didn't." He describes the

current situation of too few jobs and too many photographers as

"supply-and-demand photography".

He solved the problem for himself by simply

stopping doing "that kind of journalism". There were two primary

reasons: the first was that "the longer you spend doing it the more

likely you are to burn out. I think people like Jim Nachtwey are

unique, but I just can't do it," and the second, "I don't see the point of risking my life for the

money that contract photographers get paid."

Photographs:

[Left Page-Right] After its original use in Fortune magazine, this

image was later used in an advert. At that time the company had to

obtain model release forms for all the kids. Stone admits, "that's

not something I've ever done and I really should be doing. It's kind

of a pain in the butt."

[Left Page-Below] Approximately 40,000 people

in Cambodia have suffered amputations as a result of mine injuries

and an estimated 4 to 6 million mines are still strewn throughout

the country. These mines are usually US material from the Vietnam

war era, and Chinese, Soviet and eastern block made materials left

from the Khmer Rouge era in the 1970s and a decade of civil war

that followed in the 1980s.

[Right Page-Below] Les Stone was working in the

neighbourhood when he passed this

children's playground. He shot quite a few

pictures to get the balance of motion just

right in the final image, which wasn't easy.

Luckily the children didn’t stop swinging when

they saw him. Shot as part of the Cancer

Alleyseries for Green Peace.

Contractual obligations

He is saddened by the current state of things.

Photographers around the world have found

themselves faced with contracts that take away their

copyright and leave them with an initial sum, but

nothing in the long term. Recently the New York Times had a struggle on its hands when the establishment

drew up new contracts, which outraged many that were

asked to sign them. "Everything is nickel and dimed,

until it's almost pathological at this point. We make a

decent living, but it's not great and not near what a

middle manager would make at the New York Times."

For his own part, he's glad he never had to face the

dilemma of signing one of the work-for-hire contracts

and hates the fact that many young photographers have little choice. "It looks like a decent living. You can make

50,000 dollars a year off one picture and you get to

travel, but you don't own your work anymore." Instead

they become what he describes as "a hired finger".

He is quite unbending on the subject "It would be

an anathema to me to sign one of those contracts I

don't care what they paid." To him his work is "his

legacy, and if you don't have your legacy you don’t

have anything."

Luckily he still has a strong belief in his work and the

documentary genre. "Being part of history and

documenting history in the making that's amazing."

While he still finds that money isn't what he would like

"I'm now shooting the odd wedding to make an extra

1500-2000 dollars. It's three day rates for a magazine in

one night. There's a lot of photojournalists doing it."

he can still pick and choose the assignments he wants

to take.

Fortunate times

When Fortune magazine asked him to do a photo essay

about minor league baseball he found a story, which, like

his ethos, was driven by heart rather than money. While he sometimes had to sit for ages until the children

became accustomed to his presence, the pathos in his

finished images is striking. "You have to wait and wait

and wait for the moment to happen especially when

you've got four or five kids. One is always looking and

sometimes that isn't a bad thing. I wanted to capture the

interaction between them and the ballplayer, who they

look upon with so much pride. You have to remember

that 99 per cent of the players will never make it to the

majors, they are playing because they love the game."

The apathy of society and the media that seems to

exist at present does frustrate him. When we speak,

Hurricane Charley has just swept across Florida leaving

carnage in her wake. Further afield the Sudan situation is

escalating. Despite this Stone is still at his home in the

Catskills. He was scheduled to fly out to Africa courtesy

of ZUMA, but as worthy as the trip would be, there just

isn't the market to sell the story back home. "It would

have been 2500 bucks and I just can't do that. I'd

completely lose money it's so expensive. If it was half

I'd go, but this way it would end up costing 5000 dollars

for a week."

The assignments he does seek out are those that no

other photographer has chosen to cover. (Many other

photographers are already covering the Sudan situation,

trying to raise the world's awareness of what's going on).

Otherwise he can explore a personal project when on a

paid assignment, which was how his series Conflict

Diamond came into being. He was already in Africa

photographing a project for George Soros' Open Society

Institute. He strongly believes that, “you have to have

your own vision and ideas.”

You need only go to ZUMA Press or the zReportage

site to see a wide variety of his images. As well as extended periods in Haiti, there is his impressive body

of work on Vietnam. While working there for a story on

Agent Orange, he also began photographing the

Vietnamese troops who were celebrating 25 years since

the end of the war. He followed them as they trod the

same roads that their fathers had marched a quarter of

a century before. But before he could take a single

photograph he had to be properly accredited. "They are still completely paranoid about western media and I had

to go to the press office in Hanoi and get accredited,

which was all pretty straightforward." He returned to the

country three times while shooting the two projects. For

his ventures into the poisoned country near the Laotian

border he had to go through even more red tape.

Photographs:

[Top Left] This was shot in 1994 when the political climate was quite different

from the violence today. Stone didn't feel threatened when

photographing as most of them were play acting, although some were

deadly serious. The anger wasn't directed at him, unlike today.

[Below]

This story ran as part of AOL's Visions series and won best online

story at the POY awards. This is the heart of Agent Orange country. The

ground will be poisoned for 100s of years to come. Everything the

people eat or drink is tainted resulting in sickness in the region.

Photography projects

He was driving to the house of a girl who was infected

with Agent Orange, when he pulled over to capture

what he describes as "a typical South East Asian

moment". Two little boys were walking hand in hand

through a poisoned rice paddie. Armed with wooden

guns and elastic bands they were hunting frogs. "I snuck

up behind them. For the first couple of frames they

didn't know I was there and just kept going. Then they

noticed me, giggled and sped up, so I sped up to." The

result is a beautiful shot laced with sadness.

There is often that second or even third layer in

documentary photography. In Stone's Cancer Alley

series, which he shot for Green Peace and consequently won a POY (Picture of the Year) award, is an image of

two children on a swing in the late afternoon. The sun

has turned the photograph into a striking silhouette, but

beyond the freedom of the playground looms the

chimneys, which pump chemicals into the

neighbourhood and make the residents sick.

In their own way these images are as painful for

Stone to record as the photographs he has taken of

people being hacked up on the streets of Port Au Prince

or persecuted in Israel: subjects, which are not always

easy to talk to friends about. "I used to just sit in front of

the TV for a week before I could talk to anyone, which

wasn't good for my relationships." He knows that he and

many of his colleagues must have suffered from Post

Traumatic Stress Disorder over the years. "You can't help

it. You don’t want to be weak."

These days his wedding work, which ironically has

helped him feel less alienated, and his gardening help

him unwind at the end of project. By the time this goes

to press Les Stone will already be winging his away

across the world of another assignment.

Les Stone's hardware

Les is a dedicated Canon camera user. He was already

working with the EOS system when a year-and-a-half ago

he went fully digital. These days the only time he picks

up a roll of film is if somebody specifically requests it.

"I've become addicted to it," he happily admits about the

digital process. "And the quality is really great.” ZUMA

Press snapped up a Canon 1D Mark II for him when the

new model hit the market, and he already has a 10D

and 1D in his photographic arsenal. When on

assignment he'll slip a Lexar 1Gb CompactFlash card into

the camera and start shooting. "I don't want to use

anything bigger, because you risk using losing so much

info." When the card is full he'll download the images to

his portable Lacie 40Gb hard drive. Then every so often

he'll head back to his office, wherever that maybe on

the road, and download the images onto CDs. His

computer on these occasions is a G3 Powerbook. He

knows he should probably upgrade to a G4, and will

do eventually, but is attached to his laptop for its go

anywhere durability and memory capacity.

Les remembers, "Somebody dropped it one day and

it went flying seven or eight feet through the air and hit a

wall. I thought that was it, but when I picked it up and

opened it on the table it was absolutely fine. I'm not

sure a G4 could withstand that."

He loves Macs "I don't care for PCs" but only has

one request that they release a micro laptop similar to

Sony's Vaio, as he would buy one in a heartbeat. "I used

to carry 200 rolls of film around with me and now I

carry a Powerbook." So in his mind it all evens itself out.

Contact

Website: www.ZUMApress.com, www.zreportage.com,

Email: les@zreportage.com

Equipment

Lexar 1Gb CompactFlash

Web: www.lexar.com

Contact: 01483 722 290

Lacie Portable 40Gb Hard Drive

Web: www.lacie.com/uk/

Contact: 020 7872 8000

Canon EOS 1D Mark II

Web: www.canon.co.uk

Contact: 0870 241 2161

Mac Powerbook G4

Web: www.applestore.com

Contact: 0800 039 1010

|

|